News

In May 2014 Rebelact will organise a serie of info nights about the present situation in Egypt. Maro, a female Egyptian activist and rebel clown, will give lectures on the recent developments... More

Get Involved

Extra Info

Why we need cultural activism

Cultural activism: direct action and full spectrum resistance

By the left, quick march…

In July 2005 it seemed almost normal for me to be with 200 other people all dressed in crazy camouflage adorned with pink and green fluff, clown white on our faces and colanders on our heads. On our way to meet the Make Poverty History marchers in Edinburgh during the 2005 G8 summit to invite them to join us in taking direct action, we were trying hard to march in step with our feather dusters strung over our shoulders. OK, the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army is an absurd army but it is also a serious response to the criminalisation of protesters and dissent. So I was not prepared for the angry comments of a very serious acquaintance of mine, dressed in black: ‘This isn’t funny. We are at war and we need to be able to fight. ... You are encouraging people to think that this is a joke, and the state is very, very serious.

I’m worried. If we are at war, then it doesn’t seem that we are winning. Is my friend suggesting that our failures as a movement are partly my fault? Are all of the clowns, drummers, pink and silver ballerinas and puppeteers, the cultural activists responsible? Do we encourage people to deal with the deadliness of the state war machine in an unrealistic way? This is what runs through my mind constantly these days.

This chapter is about cultural activism and I explain this isn’t just about making things pretty, fluffy or fun. Cultural activists are taking direct action against war,ecological destruction, injustice and capitalism, but they are also constantly asking how we can act directly against their social and psychological effects. Just as military empires have defined full spectrum domination, we have embraced the idea of full spectrum resistance. After all, who can really know what it is that really inspires an individual to care, or to turn away, to give up or to rise up?

To me, cultural activism is where art, activism, performance and politics meet, mingle and interact. It builds bridges between these forms but also exists as the bridge itself, stuck permanently between two places. What links activism and art is the shared desire to create the reality that you see in your mind’s eye and believe in your capacity to build that world with your own hands.

Who am I to talk?

I see myself as part of a community which defines itself very much through its practice. Starting from what I know through personal experience, I will endeavour to expose some trends in cultural activism as well as some of its rich history which has been important to me. In doing this, I am pulling together theories that have influenced me from fields that vary widely – quantum physics, organisational psychology, postmodernism and permaculture – and have been useful in helping me to understand why this cacophony of colour, sound and dissent is vital in changing the world.

So what is cultural activism

Cultural activism is difficult to define. The definition of activism in the Oxford English Dictionary is ‘the use of vigorous campaigning to bring about political or socialchange’. But everybody from anthropologists to artists have been arguing for at least a hundred years on definitions of culture that range from the poetic to the straightforward. The noted anthropologist Clifford Geertz in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973,5) says ‘man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs’. While UNESCO in its Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity is far more direct and broadly encompassing: ‘culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and […] it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs’ (UNESCO 2001, 12). Aime Cesair, a Martiniquan writer, speaking to the World Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris is the most direct :‘Culture is everything’ (Petras and Petras 1995,54). In this sense, cultural activism could use everything as a potential resource. For me, cultural activism is campaigning and direct action that seeks to take back control of how our webs of meaning, value systems, beliefs, art and literature, everything, are created and disseminated. It is an important way to question the dominant ways of seeing things and present alternative views of the world.

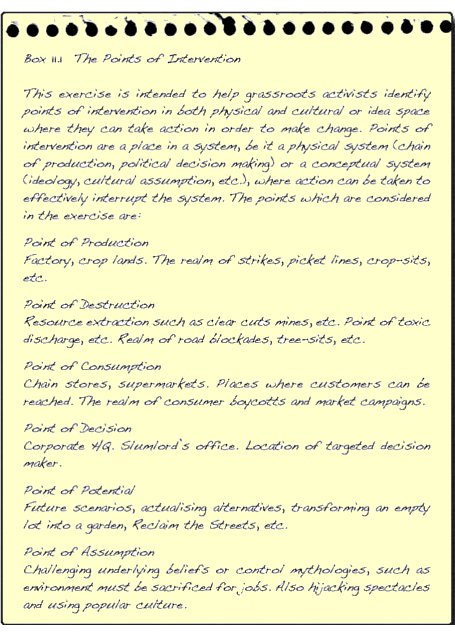

What ties together the myriad of forms that I will discuss in this chapter is that they take place not only in physical space but also in cultural or idea space. The following exercise is adapted from the Smartmeme Collective’s useful worksheet (pdf) which helps ground grassroots activists in an understanding that power structures can be successfully challenged in a variety of ways.

The old resistance of barricades, marches or armed guerrilla groups intervened frequently at the points of production, destruction or decision. The forms that we look at in this chapter are interventions at points of potential, assumption and consumption. This is a more savvy resistance which uses our media saturated society to develop new forms of actions that are ever shifting, mutating and always one step ahead of those who want to co-opt and restrain us. To understand what cultural activism means in more detail, below are some key aspects we need to consider.

Insurrectionary imagination

If you woke up one morning and decided to do something that you had never done before you would probably look for guidance. If you bake a chocolate cake you would probably get a recipe. Emboldened by your cake success you decide to build a strawbale house, so you go to the library and get a book with instructions, diagrams and pictures. Baking a cake and building a house are infinitely easier than creating a sane and just world, so how can we be expected to do it without instructions? It is no wonder that people love political manifestos that prescribe exactly how to do it. But what would happen if you sat down and visualised the world that you wanted to live in. Were you even ever taught how to visualise? Have you practiced closing your eyes and seeing a picture in your mind? What if you not only could see that picture clearly but also truly believed that you could create it in your waking life?

An insurrectionary imagination is at the heart of cultural activism. It is a sense of possibility that is not limited by copying a pattern or following a design that somebody else created or by what Augusto Boal calls the ‘cop in the head’. We all have that voice, the one that tells us our ideas are stupid, they won’t work out, they are too difficult or are bound to fail. Cultural activism relies on killing the cop in your head and expressly tries to develop this insurrectionary imagination to create performances and actions. This living practice addresses complicated questions about how we build the world that we want to live in. Insurrectionary imaginations evoke a type of activism that is rooted in the blueprints and patterns of political movements of the past but is driven by its hunger for new processes of art and protest.

Dialogue and interactivity

Giving people long sermons on the need for them to get involved in change can often be patronising and disempowering. Traditional campaigning tends to involve attempting to attract people to a cause by bombarding them with facts and fiery speeches. Cultural activism tends to move away from one-sided monologues, speeches and propaganda into porous forms that use dialogue and interaction. Is it such a huge stretch of the imagination to believe that people can speak for themselves and ultimately have something to say about the world they want to live in?

Community, concrete action and campaigning

Even though people may have passionate opinions and beliefs about the world they want to live in there are some very real obstacles that stand in the way of people organising and acting for local and global change. Psychologically, we have all experienced feelings of despondency, apathy and helplessness, while physically many of us are isolated from other people, as well from ideas, resources and information that can help us. Cultural activism, in all its varied forms tries to address these issues through:

- Community: Access to time and space free from consumerism, coercion and capitalism for conviviality, alliance building and information sharing.

- Concrete Action: Doing something, anything – whether it is repairing a billboard or hosting an open stage performance – breaks the social conditioning of complacency, despondency and apathy.

- Campaigning: Access to information that is not censored by the corporate limited media.

We can all change the world, can’t we?

The title of this book ‘Do It Yourself: A Handbook for Changing our World’ reflects a seismic shift in thought that is pervasive in many of the above forms – focusing on ‘our world’ rather than ‘the world’ and the power of the individual to create change rather than relying on the ‘masses’. Many cultural activists approach social change with an ecological perspective, viewing both movements and power structures as holistic systems where all the parts are interconnected.

In searching for political metaphors other than that of ‘the masses’ many cultural activists have embraced metaphors and paradigms that validate their beliefs that one person can change the world. The variety of cultural actions can act like:

- a lever that moves a huge boulder with very little force

- a spanner in the works of a corporate machine

- a butterfly flapping its wings that creates a hurricane.

Fritjof Capra in The Web of Life (1997, 132) explains the latter:

Chaotic systems are characterized by extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. Minute changes in the system’s initial state will lead over time to large scale consequences. In chaos theory this is known as the butterfly effect because of the half-joking assertion that a butterfly stirring the air today in Beijing can cause a storm in New York next month.This kind of metaphor of change was summed up beautifully by Patrick Reinsborough of the Smartmeme Collective: ‘what has mass impact doesn’t necessarily need masses of people’ (interview with the author, July 2006).

Roots and shoots

How has cultural activism worked out in practice over the years and in different places? There are a huge array of important influences to be looked at from political theatre to visual art, and social movements. In this section I link these historical roots with more contemporary shoots which have drawn on these historical examples in some way. I look at examples in the three areas of art, theatre and carnival that have either had strong influences on me or are part of major trends in current activist practice.

1. Fine art and public art

Roots: Muralist movement

It is doubtful that any revolution in any country ever had such a talented, perceptive group of artists to record its struggle for freedom. (Smith 1968, 281)In the 1920s, in post-revolutionary Mexico, artists such as Diego Rivera painted politically charged murals depicting scenes of the revolution and indigenous life before the conquistadors. The Mexican muralists both told the history of the nation and created a national mythology, painting on public buildings as an attempt to unite and educate the people. Jose Vasconcelos, the minister of education after the revolution, set up a network of rural art schools. His vision of Mexican identity as a ‘cosmic race’ synthesising native, European, African and Asian cultures was brought to the cultural or idea space directly in the muralist’s work. In Birth of a Nation, for example, Rufino Tamayo paints powerful images of Mexican identity, depicting a woman giving birth to a baby, half red, half white, as she is trampled under the hooves of the conquistador.

Murals reclaim public space and use it to tell and celebrate histories and struggles. The aesthetics of the Mexican Muralists have inspired artists around the Americas, Europe and Russia. The belief that the visual space in the public realm belongs to the people has fuelled directly or indirectly a wide spectrum of practices.

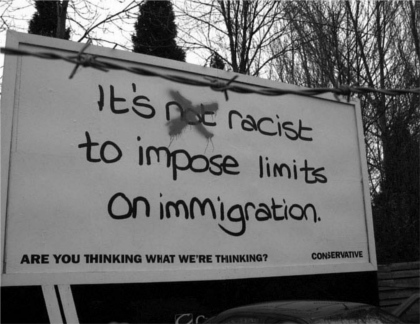

Shoots: Subvertising In the urban areas of the ‘overdeveloped’ countries, one of the most visible forms of cultural activism is anti-capitalist actions against corporate culture. Subvertising, often included under the umbrella term of ‘culture jamming’, refers to making spoofs or parodies of corporate and political advertisements in order to make a statement. Media vary from crudely altered billboards and lamp post stickers to t-shirts and TV ads. According to AdBusters, a Canadian magazine and a leading proponent of counterculture:

a ‘subvert’ mimics the look and feel of the targeted ad, promoting the classic ‘double-take’ as viewers suddenly realize they have been duped. Subverts create cognitive dissonance. It cuts through the hype and glitz of our mediated reality and, momentarily, reveals a deeper truth within.

Geert Lovink, media theorist, net critic and activist comments:

In my view culture jamming is useless fun. That’s exactly why you should do it. Commit senseless acts of beauty. But don’t think they are effective, or subversive, for that matter. The real purpose of corporation cannot be revealed by media activism. That can only be done years long, painstakingly slow, investigative journalism. Brand damage has never been proven enough. What we need is research and thinking, brainstorming, and then action. (Speed interview about media, activism & art, conducted by Andre Mesquita)

While some question the usefulness of this type of media activism it is crucially changing both idea space and public space from a corporate monologue to a dialogue where people are speaking for themselves. Pat Tinsley, the operation superintendent of Eller Media, an outdoor advertising company in Oakland, California, concedes his antagonists are disciplined. His employees have spent long hours reconstructing the altered signs. ‘It’s a high cost to us, but they are creative and use their imagination,’ he says. ‘They are very professional. They use rigs, they use the right glue, they operate at night in areas where they know there will be few cars going by. When it happens. we say, "Our friends have struck again"’.

It is not only an accessible form – billboards advertising military tattoos, four-by-fours or election propaganda are irresistible canvasses that can be ‘repaired’ with a few swooshes of a spray can. But also, the humour (at least in Oakland, California) builds bridges instead of antagonism.

2. Political theatre

Roots: Theatre of the oppressed In the early 1970s Brazilian director Augusto Boal developed a pioneering body of work which struck at the historic relationship between the stage and spectator to create an arena where oppressed people could become actors in their own liberation. In The Rainbow of the Desire (1999), Boal tells a story about his first plays – idealistic, leftist works that explained the necessity of a social revolution to workers and peasants. One day, after calling people to arms in his performance, a peasant took the message literally and suggested Boal and his troupe join him in getting weapons and killing the landlord. Boal had a hard time explaining that they were simple actors and not fighters. At that moment, he realised that he was using his theatre to ask others to do what he was not willing to do himself.

The practice that developed from this realisation is called forum theatre where a group of people from an oppressed group create a play about a specific situation. The scenario is played out with the predicted negative outcome; for example, a chauvinist man mistreating a woman or a factory owner mistreating an employee. The play is then performed for the community and the audience are ‘spectactors’. They are encouraged to interrupt the action and play out the possible changes on stage, and they rehearse the change that they want to see.

Shoots: Forum theatre ‘What defines Forum Theater as Theater of the Oppressed [is] its intention to transform the spectator into the protagnonist of the theatrical action and by this transformation to try to change society rather than just interpreting it’ (Boal 2002, 253). The shoots of Boal’s early work are in two main camps. One is the proliferation of forum theatre that is progressively removed from the performance arena into more social contexts. Forum theatre is used everywhere – from workshops in primary schools addressing bullying to community events addressing domestic violence. Groups like the Cardboard Citizens in the UK address issues of homelessness, while in Port Townsend, in the USA the Mandala Centre uses forum theatre in anti-racism work for white people.

The other main strand can be seen in character-based action performances. These forms of cultural activism involve the protesters adopting ‘characters’ for specific direct actions. Most frequently the ‘actors’ are drawn from groups that are campaigning, rather than from those with an acting or performance background. In some of the most visible groups irony is the tactic of choice: CRAP, Capitalism Represents Acceptable Practice, does action or performances where a group of (mostly) ‘non-actors’ play ‘capitalists’ carrying signs that say ‘Fuck the Third World’ and ‘bombs not bread’. These forms differ from both carnival and clowning (see below) where you strip away the masks and artifices of society, as they draw on the historic theatrical tradition of ‘character’ where you adopt the persona of somebody other than yourself.

3. Carnival

Roots: The carnival tradition ‘It is necessary to work out in our soul a firm belief in the need and possibility of a complete exit from the present order of this life’. So Mikhail Bakhtin quotes Dubrolybou in Rabelais and His World (1984, 274) to explain how carnival was necessary in the Renaissance movement to overcome the weight of the medieval cultural view of the world as unchanging.

In medieval Europe the carnival square was a place of freedom, collective ridicule of officialdom, celebration, feasting, and breaking the normal social restrictions of both hierarchy and decorum. From the seventeenth to the twentieth century there were ‘literally thousands of acts of legislation introduced which attempted to eliminate carnival and popular festivity from European life’ (Stallybrass and White 1993). In South America and the Caribbean carnival, though nominally introduced by the Catholic colonists, had taken root and flourished and married itself to African traditions of parading, costume, music and mask.

Carnival enabled people to be able to envision and believe in a different type of society and, according to Bakhtin, individual thinking and scholarly writing were not enough: ‘popular culture alone could offer this support’ (Bakhtin 1984, 275).

People who believe in carnival say it is about rehearsing what it is like to be free, a time when power is inverted and the world is turned upside down. Sceptics about carnival argue that it is catharsis, a time for the oppressed people to blow off steam so that they are willing to accept their lot in life for the rest of the year. Whichever your view, throughout history carnival has been a time for inverting the social order.

There is something carnivalesque in many of history’s unpredictable moments of rebellion, from the French revolution to the civil rights, suffragette and anti-slavery movement ‘where the village fool dresses as the king and the king waits on the pauper, where men and women wear each others’ clothing and perform each others’ roles. This inversion exposes the power structures and illuminates the processes of maintaining hierarchies; seen from a new angle, the foundations of authority are shaken up and fiipped around’ (Notes from Nowhere Collective 2004, 174–5).

Shoots: Tactical frivolity One common feature of marches and mobilisations has become carnival forms. The iconic colours of pink and silver infuse protest with playful costumes, puppets, singing, chanting and dancing. Some will say that pink and silver is making protest ‘fun’ but to me it’s about tapping into ancient forms of collective celebration, which are about inclusion and joy, something we often lack in individualised Western cultures. Music has always been a way of expressing dissent and strength when there is little other way to do it. From the chain gangs, slaves and mine workers to rastas and rappers, from punk rockers to peace ballads, trade union brass bands to the New Song movement, music and dance has been key to building social movements. Samba bands draw on a long tradition of carnival, such as the UK action samba group, Rhythms of Resistance, who use the slogan ‘Only Music Can Save Us Now’. Bands bring vibrancy to protest marches comprised of diverse people, whose outrage cannot be encapsulated in a unifying chant or slogan. Samba bands have been used to move large groups of people in street protests, to block roads and occupy buildings, and for noise demonstrations and solidarity actions outside police stations.

This brief overview shows a wide rang of examples. I want to now look at a recent phenomenon of cultural activism that I have been involved in, that of rebel clowning.

The emperor has no clothes: the emergence of the rebel clown

In the lead up to the anti-capitalist and global justice protests against the G8 summit, Scotland, in July 2005, a group of artists and activists toured the UK to apply creativity to radical social and ecological change. The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination tour was a combination of live art and a cultural resistance training camp, which combined street interventions, a nomadic information centre and two day intensive rebel clown training.

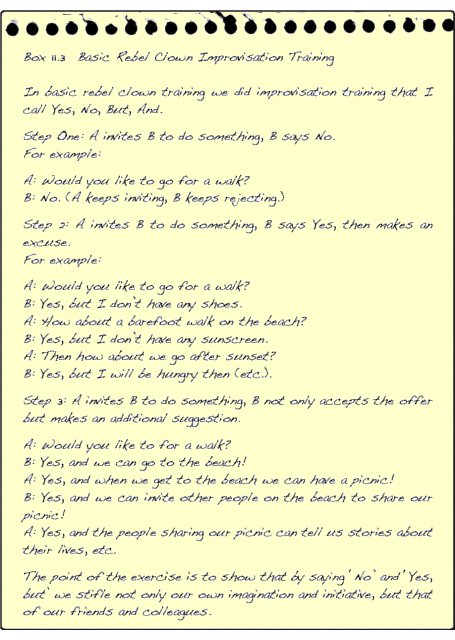

A group with more than 40 combined years of experience in clowning, collective theatre, improvisation and direct action delivered workshops designed to quickly move people towards the physical understanding of a few key concepts:

- spontaneity (to kill the ‘cop in the head’)

- complicity (to practice radical democracy and play)

- releasing the clown.

Many of the great clown teachers, like Jacques Lecoq and Phillip Gaullier, teach that everybody has at least one clown inside of them and that clown training is about ‘releasing the clown’, removing the barriers that society has put in place to keep us from our authentic self.

Rebel clowning, an emergent form that combines the ancient art of clowningwith the practice of non-violent civil disobedience, resulted from a wide variety of performers and activists saying ‘Yes and ...’. Rebel clowning is partially a tactical weapon against the sheer stupidity of capitalism and war, and partially a tool to free the self from the tremendous damage that capitalism has done to our bodies and our minds.

How does it work?

Fishing is a good example of the possibilities of rebel clowning to create both personal and political change. On the second day of clown training groups begin to learn some basic rebel clown manoeuvres. Drawing on the tradition of lazzi in commedia de l’arte, performances are improvised but the performers have some stock gags that they can repeat. Instead of stock gags, the clown army has manoeuvres. Fishing simply entails the entire group moving through space, tightly packed together doing synchronised movement. As the group turns, the person who finds themself in front becomes responsible for initiating a new movement and sound. The leader organically rotates. Practicing this physical form of rotating leadership erodes assumptions about leadership and hierarchy that are deeply ingrained in our very bodies.

One of the most magical moments I have ever seen was in the Scotland G8 protests when a group of clowns was being penned in by riot police on horses, and the clowns were fishing down the street in perfect synchronicity, clippity clop, clippity clop, clippity clop, doing a collective impression of a horse. As one of the major functions of mounted police is to intimidate protesters, the act of laughing at the horses was significant in redistributing power and agency in the situation. Unlike the story of Boal above, where the performers shy away when the farmers want to take immediate action, those of us travelling the UK, recruiting and training rebel clowns were actually calling for people to take part in impending direct actions that we ourselves would be participating in. This is an exciting development across the art and activism field, where the art in itself is inseparable from the direct action.

But how is fishing going to save the world? Having trained in exercises such as fishing, by July 2005 over 300 clowns were prepared for making decisions without a leader, as well as using physical instead of verbal communication once the protests happened. What did this lead to? Clowns appeared to be everywhere, the clowns could not be contained, the clowns as an entity had become stronger than its parts. On the other hand, a group of police went home and told the story about how, during the protests they played a game of giants, wizards and goblins with a group of clowns! Who knows where that will lead? When the convergence camp in Stirling during the G8 summit was surrounded by police, a group of clowns faced police officers who had been trained to deal with them. ‘I am not going to fall for your tricks’; a police person growled at me. Whatever we were doing, I thought, it must have been working. Clowning is dangerous because it subverts the protocols of war and policing; where ‘good’ protesters are supposed to obey authority and ‘bad’ protesters are supposed to resist with violence. It deconstructs the opposition between fluffy and violent protest. Our desire to be free is not funny, it is war. But at the same time, I still think it’s kind of funny that the state is threatened by clowns.

Consuming solutions: ‘Those fucking clowns!’ Ideas are not harmless. Activists need to be careful and question the whole nature of ideas being viral, because freedom must involve thinking for yourself. This is why real engagement and creativity is so vital to the ideas of cultural activism, and should never be let go even if it seems easier just to copy someone else’s idea. We have seen this with most forms of cultural activism – as people are hungry for answers and solutions they are quick to take up the next big trend in protest movements. While rebel clowning and clown training can be a way of healing the body and the mind from the social damage of capitalism, if it becomes a virus people will copy what they have seen either at protests, at the circus or on television. They will cut out the development of the insurrectionary imagination, and it is the development of this imagination that opens up limitless worlds of activism beyond costumes and stock gags.

There is also a long history of co-opting countercultural fashions and ideas into the mainstream by marketing professionals. Community art can be socially conservative, questioning some values, while replicating others. The idea of community art has been used as a pawn in urban ‘renewal’ to make ‘dangerous’ neighbourhoods safe for ‘development’. All too often the search for space has made artists and activists complicit in a brutal gentrification process that benefits only property developers.

New metaphors for cultural action

Emancipate yourself from mental slavery; None but ourselves can free our mind.

(Bob Marley ‘Redemption Song’)

We need new metaphors, new ideas and new images to understand ourselves and how we are going to create our everyday revolutions. And, like everything else, we are going to have to create these new metaphors ourselves. Back in the old days, with the old thinking of us versus them, people may have asked ‘how is one garden going to change the world?’ In the new times with new metaphors of ecological thinking (we are all in the same boat and it is sinking, so we better do SOMETHING!) we can understand that one garden is the world changed. All of the practical suggestions in this book, all of the gardens, health clinics and protests, are not possible unless each of us frees our minds, believes in our own potential and our own power. Capitalism does its best to make us feel helpless – ‘got to pay the rent and keep a roof over my head’ – and convince us that we need to dominate others (both as individuals and as nations) to ensure our own freedom. Cultural activism is necessary to give us all the mental and physical tools we need to free our bodies and our minds. We don’t just rehearse the revolution, we practice it everyday.

Jennifer Verson is a freelance performance activist from the USA who trains people in the art of politically subversive theatrical performances and who worked extensively with the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army touring the UK in 2005.

Published in the book "Do It Yourself. A handbook for changing our world" by Bluto Press and edited by The Trapese Collective in 2007 under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 England and Wales License.